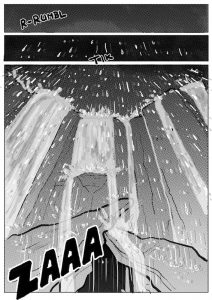

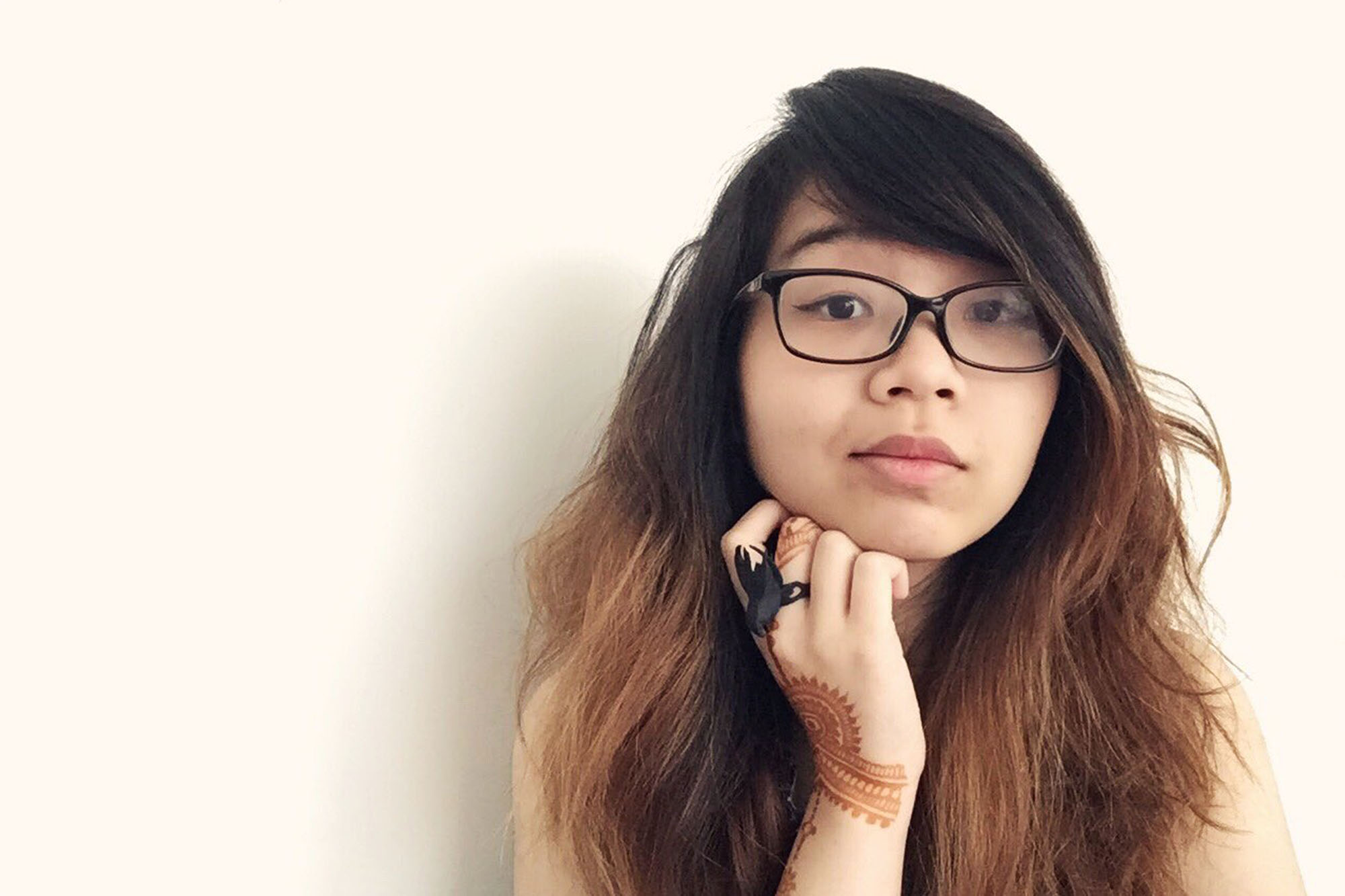

Editing is a key aspect of the publishing process that few readers ever really think about. It’s one of those things that one only notices if it is lacking or inadequate; and if done well, will be invisible. The editing of a prose book already presents its own challenges, but comics editing requires the editor to also have visual awareness. We are thrilled to have Aditi Shivaramakrishnan to shed light on this subject and talk about her experiences.

How did you become an editor?

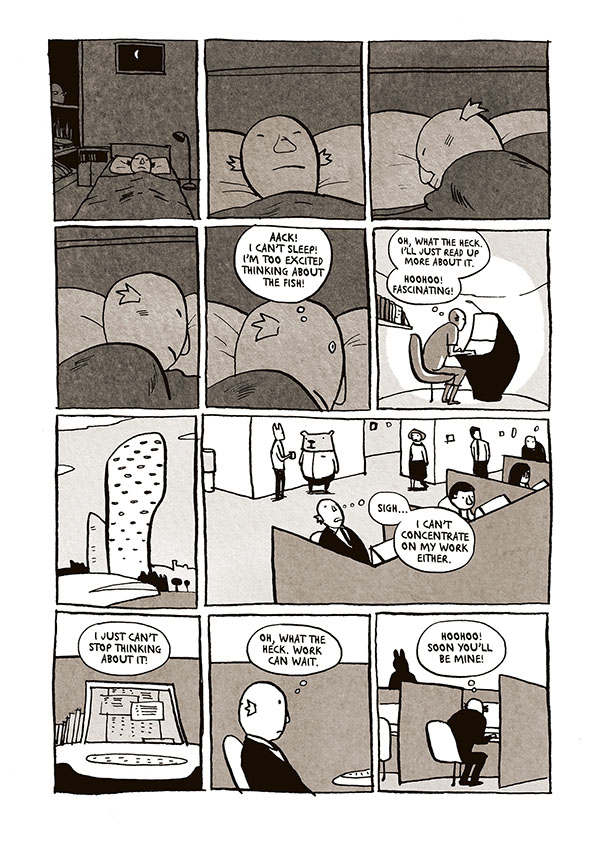

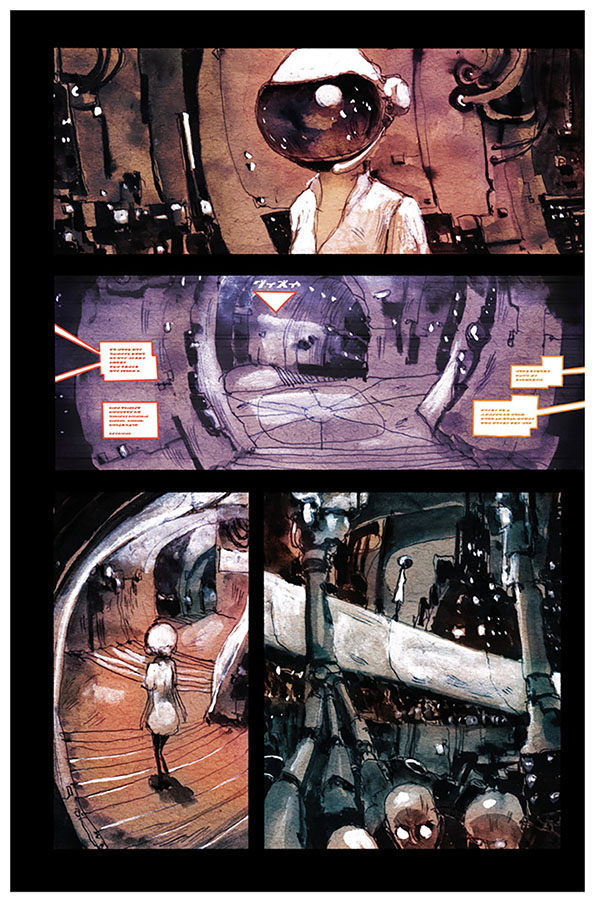

Aditi: My first full-time job after getting my BA in English was as an editorial assistant at Epigram Books. I first assisted with the Wee Editions imprint of photo books and sketchbooks, and moved on to edit young adult fiction. I never dreamed I’d get to edit comics so soon in my career but was very glad to be given the opportunity. The comic projects I worked on ranged from autobiographical and whimsical short comics, to urban fantasy, to historical events presented in the comics medium. I appreciated that diversity as well.

How would you describe your role?

Aditi: I think a good editor can pinpoint weaknesses in a work in progress and empowers the creator to develop a situation rather than immediately prescribing a fix. A good editor is also aware of the context in which a work is being produced and looks out for blind spots.

I also see my role as a liaison between the creators and the publishers, which can sometimes involve playing the role of diplomat, and as an advocate for the work. Ultimately, we’d all like to produce work that we can stand by, and that is hopefully successful by some measure.

There’s also the most practical aspects of an editor’s work: project management, personality management, time and money budgeting, and most importantly, effective communication.

More philosophically, I strongly feel there is a sense of responsibility that comes with an editor’s role, because an editor can be a gatekeeper. Even as we work, we should be aware of who is not – and whose stories are not – in the “room”, question why and strive to make space for these voices.

Much as I value beautiful writing, personally, some of the best, most memorable insights I encounter come from people — friends and strangers alike — who may not ever consider themselves Writers, they’re just expressing themselves in a conversation or in a comment thread.

In an ideal world, people’s views would be sincerely considered regardless of their grammar or vocabulary or accent. But we’re not quite there, so as someone deemed well versed in what is accepted as effective communication, as an editor I can work with people to refine their self-expression and language such that it pushes closer to the precise truth of what they want to say or show.

What’s it like working with creators? What do you enjoy the most?

Aditi: It really depends. With some, you hit it off immediately while with others, both sides take time to adapt and fall into a professional working routine. I enjoy working as an editor — and my other work as an arts manager and my informal experience as a producer — because this role involves supporting creators in bringing their vision to life. With regards to the work, the creators are usually the domain experts.

Some will be more experienced or assertive and are upfront with the editor, like I know my artwork is solid, but my grammar is not so good. Please edit me thoroughly on that front.

Other times the editor can also give suggestions on what to improve. I’ve worked with an old-school comic artist; we were putting together an anniversary edition of his book and he was minimal with explanations because he’d witnessed and produced the original comics at a time when everyone lived through that incident and understood the context. I had to assist him with filling in the gaps to provide some additional details for a new generation of readers.

My job as editor is to help creators get the project to where they want it to be, using their skill. If the intended ending point is Z, and we face problems along the way, I enjoy the process of collaboratively finding solutions to those problems through discussions.

Ideally, I like to ask clarifying questions rather than doling out prescriptions with a heavy hand unless the work or the author really requires it. I think there’s a fine balance an editor must strike between flagging problems and allowing the writer space to brainstorm and respond with a fix, versus being able to offer up solutions if needed.

I like when I can just say to the creator, OK, talk me through what you have in mind. Then I can repeat it back to them, OK this is what I got from what you said, in my own words. Is it accurate? And depending on whether it’s a yes or no, from there we can proceed or work on it some more.

What is the weirdest thing you have had to do as an editor?

Aditi: I specifically remember Googling “how long does a corpse float in seawater” (for a mystery series — YA, no less).

But what has moved me more is the weird intimacies that can form between an editor and writer; the work doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it’s part of real life. I was once checking an FA (Final Art) and got a call from the author about editing the acknowledgements as they’d just ended a relationship, and I was like, okay, copy that, but how are you doing?

I chanced upon this Tweet the other day by Jini Maxwell, co-editor of The Lifted Brow, that I thought articulated this well, that editors too have a “duty of care”.

What do you read for pleasure and how do you read your books? Do you also “read for work”, keeping tabs on particular genres to stay on trend?

Aditi: I read a lot of new releases in contemporary fiction, particularly by writers of colour; these days I’m also reading more works translated into English.

I’ve always enjoyed reading as a solitary activity but that has solidified in my adult life; when younger I engaged a lot with online fandom, and then as a literature student I’d discuss texts with coursemates, and while I worked full-time in publishing, with my colleagues. I find that I’ve always most “effectively” read when I’m not precious about it — a luxury a time-strapped literature student juggling multiple texts a week didn’t have.

Sometimes the #bookstagram worthy cafe is just distracting or stifling. Or like, I took Middlemarch with me to Bali recently but found I much preferred playing with the puppies on the beach…

I’m a fan of the OverDrive mobile app which lets you read e-books loaned from the library. It’s great for reading while commuting and I don’t have to carry around a 720-page copy of A Little Life.

I try to borrow books from the library and then purchase my own copy if I’d like it for my collection — motivated primarily by bookshelf space — but I’ll buy a book upfront if I want to support the creator or if I can’t wait my turn in the library reservations queue. Or sometimes, I’m bedazzled by a compelling cover and somehow find I’ve already handed over my money.

Yes, I do “read for work”, which has variously involved reading young adult fiction, comics, archival material, photo books and digital marketing guides. I always feel like I should do more.

That being said, I tend to naturally draw connections between things I’m encountering at any given time, including films and conversations (I’m a big fan of overheard conversations). Or, I’ll be drawn to a certain theme or topic for a period, and I think it can be valuable to learn and reflect that way as well.

What sort of stories/comics would you like to see coming from Southeast Asia?

Aditi: My instinctive answer is that I’d love to see stories drawn from Southeast Asian histories and mythologies — there’s so much there. I’d also love to see narratives that speak to the true diversity of Southeast Asia — geographically, socio-economically, linguistically, culinarily — and for the creators to come from all parts of the region.

I bet a lot of this exists already, with an audience, it’s just that I haven’t encountered it yet, perhaps because it’s not written in English.

But what I’d ideally love is for it to reach a stage where Southeast Asian creators don’t feel they have to tell stories that all tap into all that; there’s something frustrating about feeling the pressure to serve up past traumas or exotifying our culture for consumption.

They’ll have as much freedom as Western creators to tell everyday stories like characters having adventures, solving mysteries, falling in love, hurting each other…basically, living their lives.

Wow, that’s some great insight you’ve given us. Thank you for sharing.