During these pandemic times, you have probably encountered short comics or infographics on social media about COVID-19, such as illustrator Kow Wei Man’s viral infocomics on staying safe during the pandemic, or The COVID-19 Chronicles, an ongoing educational comic series by NUS Yoo Loo Lin School of Medicine.

These comics may differ in style and presentation, and they may be created by artists with different backgrounds, but they do have one thing in common: They inform and engage the audience on medical topics through a confluence of art and science.

You may wonder, in a field dominated by hard science and numbers, what role can art play?

Say hello to graphic medicine.

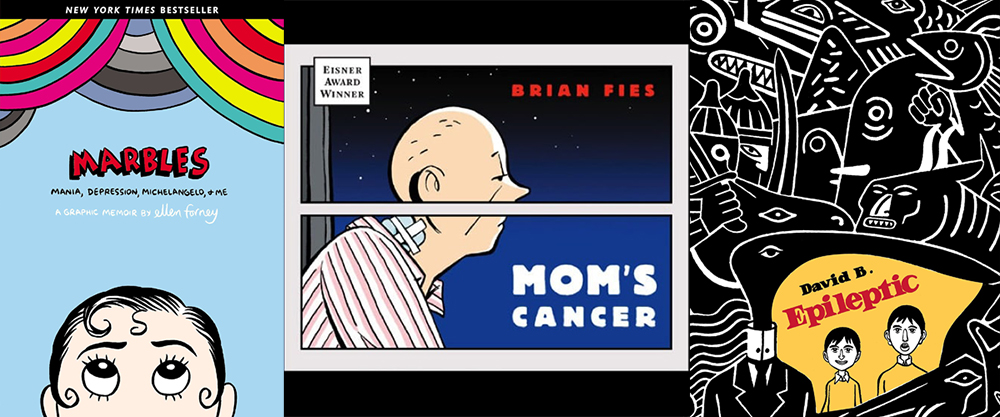

Graphic medicine covers a berth of medical conditions written from various perspectives. Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me talks about mental illnesses, Mom’s Cancer delves into a cancer narrative, and Epileptic discusses the stigma of epilepsy.

What is graphic medicine?

Graphic medicine draws its meaning from its two halves: It is the union between graphic novels, and medical education and patient care.

It is a great example of how art reconciles science with humanity, where you don’t merely treat the ailment; you treat the person behind the illness too.

This pandemic is not the first time comics has collaborated with medicine – comics have explored medicine-related topics since the early 1800s!

Despite that, the term “graphic medicine” was only created in 2007 by Dr. Ian Williams. Following this, multiple universities have started including graphic medicine in their curriculum.

Not restricted to factual and informational pieces, these graphic novels often draw upon lived experiences of all parties involved – patients, medical professionals, and caregivers – to offer audiences personal glimpses into perspectives and situations they might not otherwise have.

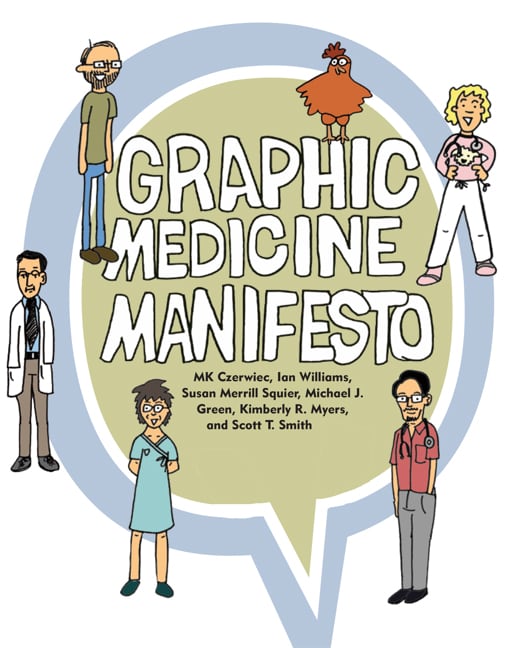

Graphic medicine can help reconnect medical science and illnesses with the people who have those conditions. Graphic Medicine Manifesto serves as a primer for anyone interested in graphic medicine.

Why graphic medicine?

Conventionally, medicine tends to endorse an isolated biomedical approach almost exclusively. Diagnose patients, pinpoint treatments, monitor recovery processes, and send patients on their merry way. Rinse and repeat. The replicability of this cut-and-dried approach makes it highly efficient.

However, today’s practitioners are increasingly aware of how this approach ignores the human and emotional aspects of medicine of patients’ recovery experiences. When you atomise and delineate patients into body systems, it is no surprise that they feel disconnected and less satisfied with the care received.

Pivoting to a human-centric medical approach, graphic medicine reconnects humans with science: medical professionals with patients; pathology with empathy; biology with biography.

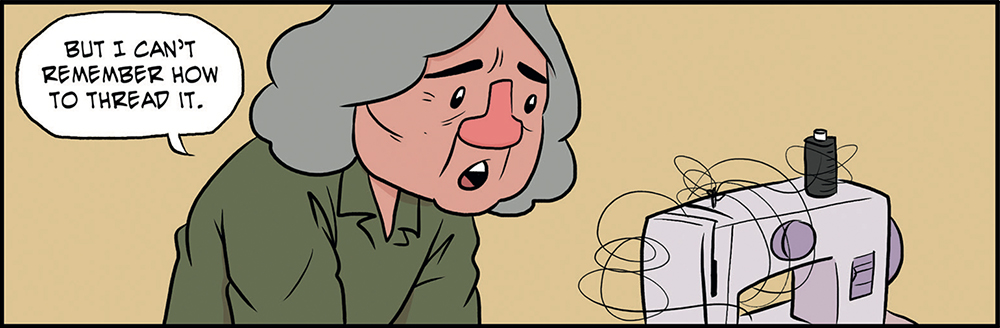

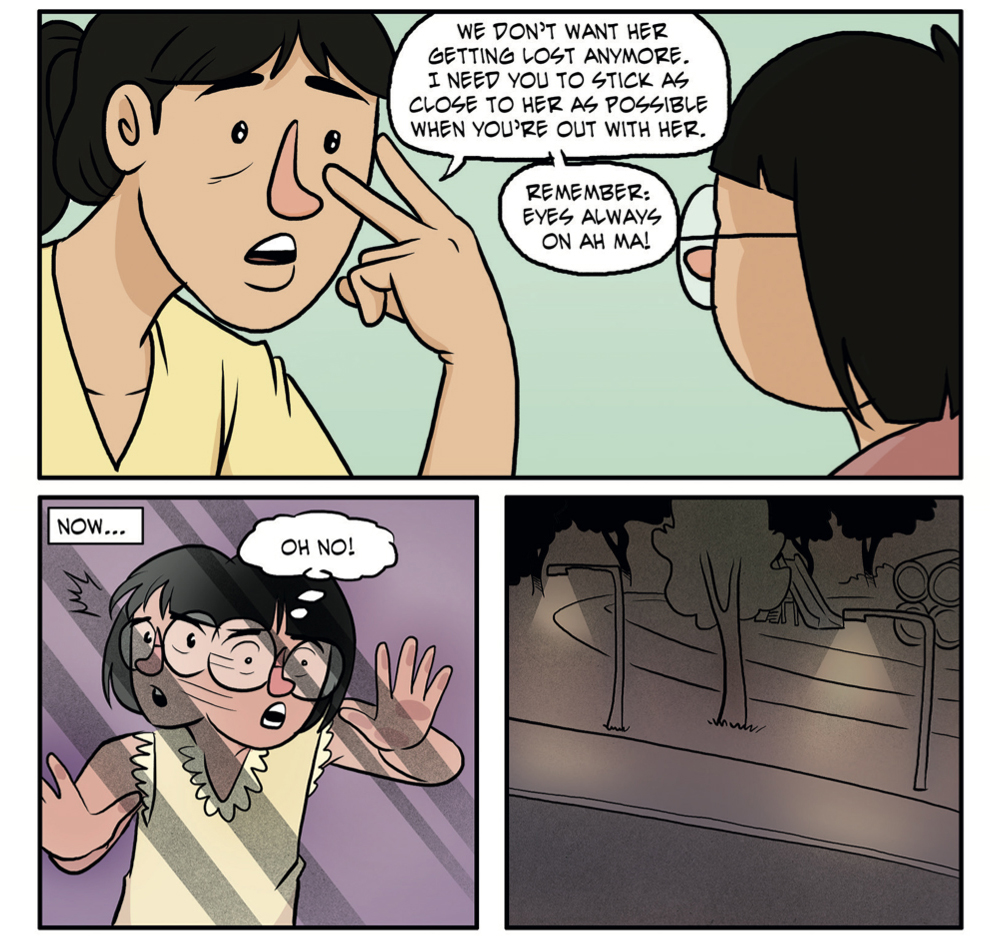

Dementia is the cognitive decline of the brain outside the realm of normal ageing. (Panels from Amazing Ash & Superhero Ah Ma)

What is dementia?

While almost any medical case can benefit from graphic medicine. Two characteristics in particular make a condition a good candidate for graphic medicine: stigmatisation or marginalisation, and a chronic or devastating nature.

Dementia meets both these criteria.

Dementia refers to the cognitive decline of the brain outside the realm of normal ageing. Persons with Dementia (PWD) gradually lose their ability to perform day-to-day activities. Dementia does not refer to a specific condition, and is instead an umbrella term covering specific types of decline, including Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Dementia.

As the global ageing population increases, so does the incidence of dementia. In 2018, the WHO reported that there were 50 million people affected by dementia. That’s the equivalent of a person developing dementia every 3 seconds! This explains why there is growing interest in using the arts – including graphic medicine! – to help foster a positive living experience with dementia.

Graphic medicine can help fight against the stigmatisation of dementia by humanising the people behind the condition. (Panels from All That Remains; part of project Forget Us Not)

How does graphic medicine help PWD?

Despite its growing prevalence, and due to its irreversible nature and cumulatively debilitating impact, dementia remains a taboo subject in many places.

One of the biggest barriers PWD face is stigmatisation stemming from a lack of information and understanding of the condition. Dementia is more than just its biomedical dimension – it is indelibly linked to the person experiencing the condition: physically, mentally, and emotionally.

The impact of this stigma is multifold – PWD might be left feeling dehumanised not only by outsiders, but also by some medical professionals. When discrimination underpins social cultures of shame and embarrassment, it can create resistance for people to seek medical attention, even if they are already experiencing symptoms. Moreover, those who support PWD are affected by the stigma as well.

All these make graphic medicine especially pertinent in improving the welfare of PWD and those around them.

Because of the complex nature of dementia, graphic novels can blend the visual and textual to create layers of subtleties that go beyond the biomedical. (Panels from Amazing Ash & Superhero Ah Ma)

Graphic medicine can address discrimination of PWD not only by providing information on the condition, but also by evoking a human-centred depiction of the medical experience. When readers engage with images of PWD, be it through factual or fictional means, they develop a multifaceted, holistic understanding of the condition beyond the biomedical.

Besides making topics more intellectually approachable, graphic novels offer another form of accessibility – emotional accessibility. By interweaving meaning and context to things typically invisible or difficult to describe in traditional text, emotional perspectives are added back into the equation.

This collective weaving of information – medical, social, cultural, and emotional – builds a living, breathing image of dementia rooted in our everyday lives. The knowledge this is a condition affecting people like us then becomes the foundation – not the exception – upon which new understandings are built.

Moments difficult to inscribe in the harshness of text – including the prejudice PWD face, difficulty in communication, or embarrassment felt when needing help for intimate daily activities – can be coded into the dance of words and images. The relational and temporal aspects of narratives can exist between the spatial and literal. During the reading process, graphic medicine engages the audience, and encourages reflection upon the realities of the characters.

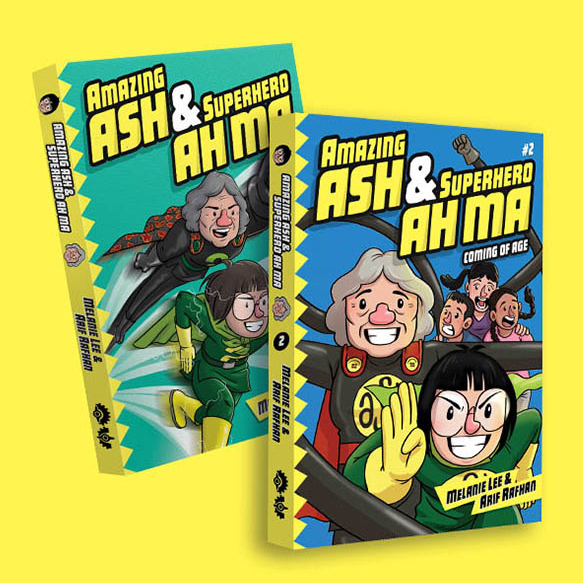

Amazing Ash & Superhero Ah Ma (Books 1 and 2)

We suggest you start your foray into graphic medicine with Amazing Ash & Superhero Ah Ma – an accessible and heartwarming story about how Ash and her grandmother handle the challenges of ageing and dementia while leading an exciting double life as superheroes. Even as Ah Ma’s dementia progresses, she continues to take all her responsibilities seriously – taking care of her neighbourhood, and being a mentor figure to Ash.

The book explores how having a support structure of not merely the immediate family, but a wider social circle as well, can help alleviate some of the stresses of living with dementia. Through the support of her family and the community, Ah Ma is able to continue living comfortably in a familiar environment without hindrance to her well-being or independence. She is still Superhero Ah Ma – dementia is just one of many things she contends with in her day.

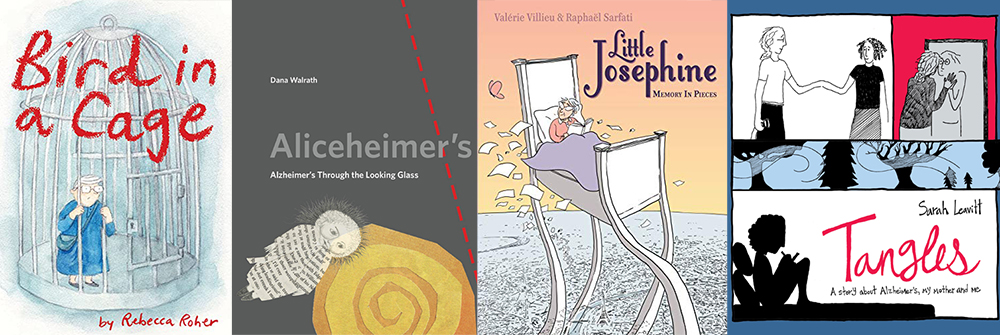

In recent years, graphic novels have become increasingly popular outlets for caregivers to navigate the psychosocial aspects of their responsibilities. Framed through a personal and emotional lens, works such as Bird in a Cage, Aliceheimer’s, Little Josephine: A Memory in Pieces, and Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother and Me offer outsiders intimate glimpses into the realities of caring for PWD.

Caring for PWD can be a physically and emotionally challenging task: Beyond fatigue from helping with their everyday needs, caregivers need to deal with behavioural changes and the emotional impact of witnessing the deterioration of a loved one’s condition.

Some caregivers turn to writing as a form of catharsis. Dana Walrath’s journey in creating Aliceheimer’s is relatable to many caregivers: It is a healing process, and one that can hopefully be extended to changing wider societal stigma on the narrative of ageing and dementia.

Others lean in to graphic medicine’s ability to educate and inform. Little Josephine: A Memory in Pieces delves into the shared emotional connection between nurse-author Valérie Villieu and her elderly patient Josephine, and reminds fellow medical practitioners of the importance of compassion and empathy in their practice.

Regardless of the perspective, graphic medicine is an invaluable source of information, comfort, and empowerment for many individuals and communities.

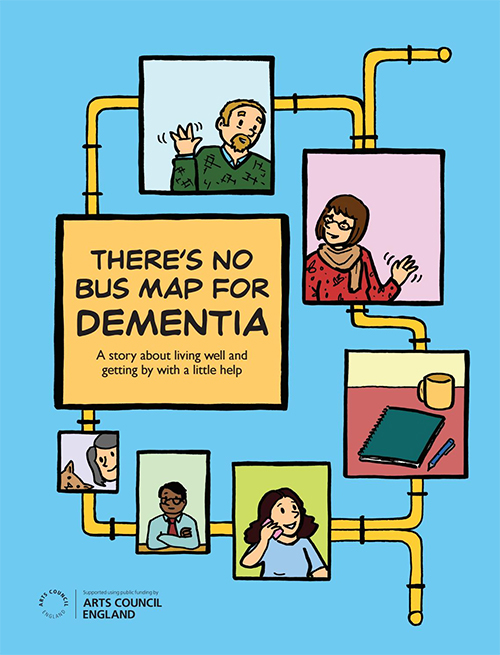

More efforts have been made in recent years to amplify the voices of PWD in graphic medicine.

Efforts have also been made to fund projects covering dementia from the perspective of PWD. While stories by caregivers remain essential in creating public awareness and empathy, there is still a gap in understanding of how those who with the condition wish to be portrayed.

Working with a group of PWD, the Beth Johnson Foundation created There’s No Bus Map for Dementia, a graphic novel that focuses on the daily realities of living with dementia. More importantly, instead of relegating the voices of PWD to the background, this work amplifies the voices of those with the condition. The result is a tale of joy and hope; friendship and independence.

Over time, the project hopes more works of similar nature can be produced, and more stories of dementia can be told in the way PWD want: with respect, and as people with agency.

Graphic medicine resources

For a comprehensive list of other graphic novels and more information on graphic medicine, visit the Graphic Medicine International Collective. We have also handpicked some other reference sources for your foray into graphic medicine!

https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/graphicmedicine/index.html

https://www.statnews.com/2018/04/26/using-comics-in-medicine/

![[PRESS RELEASE] Difference Engine Unveils 2024 Catalogue](https://differenceengine.sg/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/DE-Catalogue_1200x480.png)